For some writers, just getting the story started is the toughest part. There’s so much you want to say, but you have to ease the reader into it while keeping them hooked. In this article, I will examine exposition, the first stage of Freytag’s Pyramid, give some examples, and finally, I will offer a Story Weapon to give your stories a strong start and capture your audience’s attention.

This article introduces Freytag’s Pyramid as a classic story structure model and focuses on its first stage — exposition — which establishes the world, characters, tone, and central dilemma of a story. It explains how to craft strong exposition with examples, tips, and common pitfalls, showing how it naturally leads into the inciting incident and rising action.

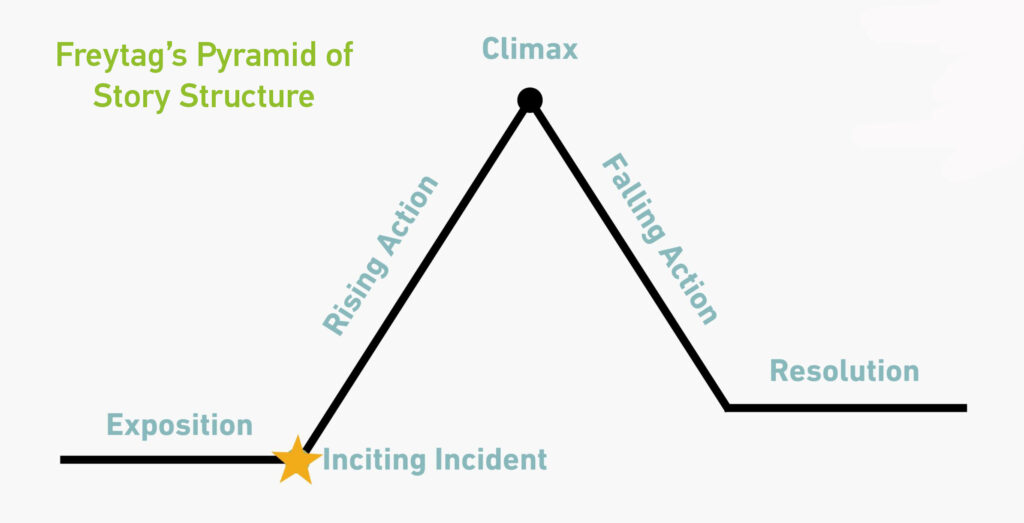

5 stages of Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid is a story structure developed by German novelist Gustav Freytag. It consists of five key stages, which include exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution in that order. You can use these stages to your advantage to build your own tales and narratives.

Mastering story structure is the key to becoming a successful and prolific writer.

What is exposition?

Exposition is the first stage or Act One of Freytag’s Pyramid. It serves as an introduction to the world and the story by providing the setting, the time, and the place in which the story takes place, as well as introducing the reader to the characters and main themes.

You can also share character backstories here to build a deeper sense of relatability between them and the reader and hook them from the get-go.

Exposition introduces the conflict

An essential part of the exposition section is that it sets up the primary conflict, paving the way for the rest of the story. The exposition sets up the status quo or “ordinary world” while simultaneously dramatizing the protagonist’s dilemma that leads to their inciting incident.

For example, Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2002 opens with a very effective exposition phase. It introduces Peter Parker, the protagonist, as well as other main characters. We see Peter’s life as an average high school student, and how he lives with Uncle Ben and Aunt May. It also lays the foundation for Peter’s arc through Uncle Ben’s speech that “with great power comes great responsibility.”

Core elements of a strong exposition

Let’s break down what makes for strong exposition and find out what you need to consider when writing your own story.

- Setting: This is the time, place, and environment in which the story takes place. Your story could be set in modern-day New York, Medieval France, or a fantastical world like Middle-earth. The exposition should deliver that information effectively.

- Characters: Tell the audience who your characters are, depict their motivations, and hint at what’s at stake for them.

- Tone and genre: A story should represent its genre and already be setting up the tone and theme (dramatic question) at this point. This will give you ample time and space to explore them further later on. It also helps your audience understand the type of story they are reading.

- Context and backstory: You want to avoid an “info dump,” but you can find creative ways to disguise exposition by dramatizing the backstory of your characters through actions. By the time you reach the Inciting Incident the reader should understand what the story is about. In order to assure this, you must make sure that your theme supports the Inciting Incident. For instance, in Romeo and Juliet, if we don’t experience Romeo’s heartbreak over Rosaline in the opening and his questioning of whether or not true love exists, there will be no context for what it means when he sees Juliet at the Inciting Incident.

- Planting the seed of conflict: Lastly, the exposition should also lay the foundation for the conflict that is to come. You don’t need to fully reveal the threat, but hint at it to prepare the readers emotionally and logically for the rising action.

Examples of effective exposition

There have been numerous examples of effective exposition in film, TV, and books. Let’s take a look and see what we can learn from them.

Shrek

Shrek is a perfect example of exposition done right. The movie begins with a stereotypical fairy tale, before the protagonist, Shrek, tears the page from the storybook and uses it as toilet paper. It instantly shows that this movie is a juxtaposition of classic fairy tale tropes, and we are introduced to Shrek the ogre, who lives alone in his swamp in a fantasy world.

We see Shrek enjoying his time, and learn more about his personality. His attachment to his swamp also sets up the conflict with Lord Farquaad later in the movie as his land gets seized. The exposition tells us everything we need to know from the protagonist, the themes, the place, and the central conflict.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

The Fellowship of the Ring has brilliant exposition, both in the original novel and the movie adaptation. In both, we meet Frodo Baggins as well as the wizard Gandalf. It sets the story in the fantasy world of Middle-earth, and shows what’s at stake.

The book starts off small with the preparations for Bilbo and Frodo’s joint birthday party, a magnanimous event for the Shire folk, then gradually introduces the One Ring and the source of conflict that expands over the rest of the trilogy.

In the movie adaptation, there are multiple scenes depicting the history of Middle-earth and the past struggle against Sauron to provide further context for the audience in sharp visual contrast with the lush and peaceful Shire.

The Hunger Games

In Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, we are quickly immersed in a dystopian world where people live in harsh conditions divided into multiple districts. The protagonist, Katniss Everdeen, lives in the impoverished District 12, and we are immediately shown the tough life she lives as a provider.

We are also introduced to other main characters like her sister Prim and her love interest, Gale, along with the concept of the Hunger Games. The exposition perfectly portrays dark and tense tones as the audience learns of the horrific games that rule Panem.

The Great Gatsby

Here the exposition comes from Nick Carraway’s first-person narration as he recounts his experiences with Gatsby in the summer of 1922. The exposition also tells us what he’s observed about Gatsby’s mysterious wealth, setting up a core conflict while introducing these two men and Nick’s cousin, Daisy.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Long prologues: In most cases, long prologues are boring. People want to get to the meat of the story. Structure your exposition in a way that keeps the reader’s interest.

- Starting with little to no tension: The exposition phase of Freytag’s Pyramid is designed to introduce the main conflict. You can be a little subtle or take a more direct approach, but leaving out the conflict means that the beginning of your story is incomplete.

- Too much at once: You’ve made a beautiful world and are eager to share it, but take it a piece at a time. Introduce your characters, places, and concepts naturally. Avoid showing them all off at once, as it can be confusing and hinder the reader’s attachment to your main characters.

- Flat tone or no voice: Maybe you’ve written an amazing inciting incident to kick off the action, and think, “They just have to get through the first bit to understand X, then they’ll love it.” But the exposition is a vital part of the story. Your readers might never make it to the “good bit” if you don’t hook them from the start.

Your story weapon: How to write a strong exposition

Exposition is the foundation of every great story. It orients your readers in the world you’ve created, introduces them to the characters they’ll care about, and plants the seeds of the dilemma that will drive your story.

When done well, exposition doesn’t just spill facts — it captivates. Master this first stage of Freytag’s Pyramid, and your story will unfold with clarity, momentum, and purpose.

Here are some things to consider in writing a compelling opening that will be keep your reader turning the page:

- Spark interest: Hook your reader by leading us to wonder, i.e., “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” The first paragraphs and scenes are crucial to hooking your reader. Give us something to care about from the very beginning.

- Show, don’t tell: This is a classic tip that you should always follow. Long expository dumps delivered in monologues or uninteresting ways are dull. Instead, reveal backstories and context through the actions of your characters. And remember, particularly in the beginning, you do not need to show us every blade of grass for us to know it is a lawn.

- Focus on what’s relevant: In many stories, especially those that have detailed world-building, it is better to give small, bite-sized pieces of information to the audience. This is more manageable and does not overwhelm the reader. As they continue to read, they will be exposed to new information as it becomes relevant. (And don’t introduce too many characters at once. We can only become invested in that which we have experienced.)

- Build curiosity: There need to be some unanswered questions at this stage. When writing your exposition, you can introduce some key elements but leave them unexplored until later in the story.

Find out more in one of my workshops – The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, Story Day