Flashbacks are one of the most powerful tools you can use to reveal the deeper layers of a character’s life. They allow you to momentarily break free from the linear timeline, opening a door into the past to illuminate the emotional truths, motivations, and formative experiences that shape your characters in the present.

When used intentionally, a flashback doesn’t interrupt the story—it enriches it, deepening the narrative and giving your audience a more complete understanding of what drives your characters and why their choices matter. In this article, I’ll look at the definition of what a flashback is, explore its different uses, give an example of how you can use them to build meaning, and finally I’ll offer you a Story Weapon to find the right moments for flashbacks.

Flashbacks let you break the linear timeline to reveal key past events that deepen character understanding. When used purposefully, they enrich the narrative rather than disrupt it.

Definition of a flashback

A flashback can be defined as a scene that take place before the events of the story but are revealed as the story progresses.

This isn’t exactly a memory, or a throwaway line like, “Billy remembered his mother saying the same thing when he was growing up.” Rather, flashbacks are their own “present moments.” For a few paragraphs, pages, or chapters, we’re taken beyond the linear flow and transported to a moment that’s already occurred.

“In hindsight, I realized I could see into the future. Which is kind of like having premonitions of flashbacks.”

– Steven Wright

What’s the purpose of a flashback?

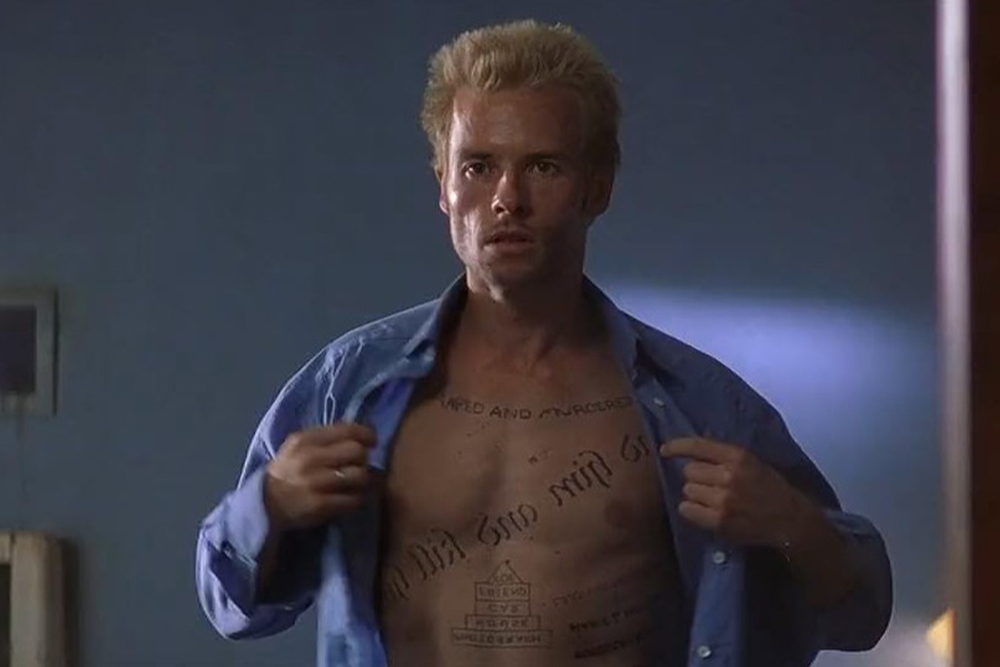

Let’s explore some of the structural benefits that a flashback provides. In film and television, flashbacks are so common that we’re accustomed to stories taking place in a non-chronological order. An extreme example is Memento, written and directed by Christopher Nolan, in which most of the information is presented in flashbacks or outside the normal flow of time.

Dramatizing Exposition

Flashbacks are often used as a way to dramatize exposition in order to provide context for the present drama. Rather than simply telling the reader that Bill was orphaned at five and joined the circus, it is more impactful to take the reader or audience back for a moment to show it.

Immediacy of Experience

A flashback provides a sense of immediacy. It takes the reader or audience out of the abstract and gives them a visceral experience of the character’s situation. By taking the reader back to the “scene of the crime,” i.e., the significant moment you want them to experience, they can remain involved in the drama.

Advancing the Narrative

When there is an essential scene that happens prior to the story’s beginning, a flashback is often the surest way to advance the narrative.

This is commonly used in mystery movies and TV shows, for example, to visually play out the innocence or villainy of different suspects for the audience as detectives work through the clues.

Flashbacks are tied to impactful moments

It’s interesting to note that most memories are never actually dredged up at all, but simply return again and again. For instance, when one’s heart is closed due to an emotionally painful experience, it only opens when a similar situation arises again.

In those moments, we realize that the hurt is still there and some part of us is still negotiating with it. Thus, engaging in a new relationship often involves flashbacks to the old one and ironically, in an attempt to forget the past, one has to remember it.

Emotional triggers

For characters experiencing PTSD, this is especially true. The most common example is that of soldiers returning home from war. Their bodies have experienced such intense stress that their minds are now focused on the possibility of it happening again. Random events can trigger this, loud sounds, bright flashing lights, and it can reignite the trauma experience.

This is a key part of writing a flashback. There tends to be an emotional trigger that then also ties the reader to the flashback. The character in question no longer has their feet firmly planted in the present. Rather, they are taken to an earlier time where the past becomes present again.

How to give context to flashbacks

When including flashbacks in your story, it helps to be mindful of how a memory can change a person’s understanding of the present moment.

Let’s consider the following situation:

Sadie was suddenly aware of a moment she had forgotten. Thirteen years ago, she stood in the living room and watched her mother mock her brother Paul for his stutter. And Sadie, not understanding the depth of her mother’s cruelty and wanting the family to be reunited, went after Paul and insisted that he “grow up and get over” it so they could all enjoy Christmas.

Here are examples of how this flashback could be dramatically summoned.

- Sadie’s mother is on her death bed, and she asks Sadie why Paul has never come to visit. And then, we flash back to the scene so there is context for mother’s question.

- Sadie has spent her life taking care of her mother. And her mother’s dying words are “Sadie, why didn’t you amount to anything?” Suddenly, Sadie realizes that her brother Paul did the right thing by leaving. Even though it was painful, it did not cost him his dreams.

Besides the structural advantages, it’s helpful to think about the way that we parse past from present. Let’s lean on this idea from writer and director Charlie Kaufman:

As I move through time, things change. I change, the world changes. The way the world sees me changes. I age, I fail, I succeed, I am lost, I have a moment of calm. The remnants of who I have been, however, hover, depress me, embarrass me, make me wistful. The inkling of who I will be depresses me, makes me hopeful, scares me, embarrasses me. And here I stand at this crossroads always embarrassed, wistful, depressed, angry, longing, looking back, looking forward. I may make a decision and move from that crossroads, at which point I find myself instantly at another crossroads. Therefore, there is only movement.

The only place that time flows chronologically is in history textbooks. The actual experience of life is much more temporally fluid.

Your story weapon: Keep the trigger ready

Think about the big moments in the lives of your characters. Sketch out what happened and keep a short list as you go along. Look for those triggering moments. You might suddenly find the right scene to bring back a memory. It could only be a brief flash at first, building into a longer flashback as the character is further reminded of their past throughout the story. You can use this to build up the drama for your readers.

Even though we’re only visiting the lives of these characters for a period of time, their past comes with them. When you decide to write a flashback or two, we’ll happily visit the past with you.

What would trigger a flashback in your characters? What are their primal motivations? Dig in deep in one of my workshops: The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, Story Day