What happens after a story’s climactic moment? What comes after the protagonist wins the girl, or defeats the bully, or triumphs over evil? The best stories keep the reader (or audience) guessing until the very end.

The screen doesn’t cut to black when the One Ring falls into the fire. Sauron may have been defeated but the story isn’t over. In this article, I will explain what “falling action” is, and why it is an essential part of any well told story. We will explore its necessity in bringing closure to the narrative by resolving the dramatic question. Then, I’ll give you a Story Weapon to help lead you to writing a satisfying conclusion.

Falling action is the brief phase after a story’s climax where tension resolves, loose ends are tied up, and the protagonist’s transformation is revealed as they adapt to their new reality. It provides emotional closure and thematic depth, showing how the character has changed and what they’ve learned before the story concludes.

What is falling action?

Falling action is the term used for the part of the story that leads to the end, sometimes called the “new equilibrium.” It immediately follows the climax, resolving the tension from the protagonist’s dilemma, and the story transitions to its close.

Think of it as the calm after the storm. It differs from the conclusion as it is not the final event of the story but rather the transitional stage where the author begins to tie up the loose ends remaining from the big reveal of the climax.

5 stages of plot

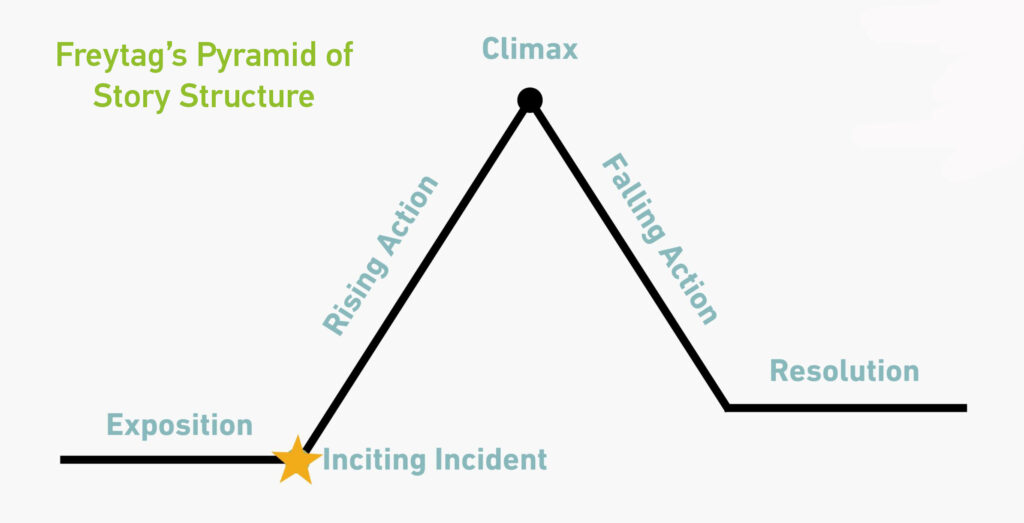

The term “falling action” was first coined by Gustav Freytag, a 19th century German writer, who introduced Freytag’s Pyramid. He theorized that all plots can be broken into five key stages: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. As you can see from his pyramid, he shows that the climax is about two-thirds of the way through the narrative.

While I agree with his basic premise, I think his sense of proportion is a little off — the climax happens quite a bit later, right towards the end of the story. After the climax, the storyteller typically wants to tie up the loose ends as quickly as possible. Have you ever been to a movie where they defeat the bad guy and the story just keeps going? The audience tends to get restless and starts heading for the exit pretty quickly after the climax has occurred.

The falling action typically takes up approximately the final 5% or so of the narrative before the conclusion.

While Freytag introduced the idea of the five-stage story structure, writers over time have taken his original pyramid and adjusted it to their story’s needs. They no longer subscribe to the limited pacing of the five step story. Many have taken his structure and even omitted the falling action step entirely.

How to spot falling action

The climax typically resolves the protagonist’s central dilemma but doesn’t answer all of the plot questions. Falling action can be used to show the characters mending relationships, solving leftover mysteries, or coming to terms with their newfound understanding of their dilemma.

For example, although your protagonist has changed, the world around them often remains the same. The reader wants to experience how the protagonist has adapted to their new reality within the framework of this new worldview.

Falling action vs Conclusion

Because it is transitionary in nature, it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish the falling action from the conclusion. In fact, some stories have very little falling action prior to the conclusion. Though rare, it is possible to tie up the loose ends prior to the climax, thus the climax leads directly to the conclusion of the story.

In The Wizard of Oz, for example, the climax occurs when Dorothy kills the Wicked Witch of the West but she is still “trapped” in Oz, and doesn’t yet understand that she has held the power to get home all along. It is only in the falling action that she is led to this discovery. All she has to do is click her heels and return home. This leads to the conclusion where she discovers it was all a dream, and that, “There’s no place like home.”

Pacing

The pacing tends to slow in the falling action as the characters sift through the dust of the climax. This ultimately transitions into a final conclusion where the reader experiences the protagonist “returned home.”

Purpose of the falling action

Depending on the type of work you are writing, your story may do better without a falling action. Plot-driven stories like thrillers, action or mysteries, often end abruptly following the climax. Highly-charged stories tend to lose their narrative drive quickly once the hero is safe and peace has been restored.

With character-driven stories however, authors use falling action to bring closure to the reader. After investing in the complexity of the characters’ lives, the reader craves greater emotional resolution.

Falling action resolves conflict

The author can use this time to tie up any loose ends, but they may also choose to leave some questions open-ended, unanswered or even ambiguous, depending on the dramatic questions that was established in the beginning of the story. Even a tragic story has a falling action in which the reader or audience experiences the resulting consequence of the protagonist’s fatal choice.

Emphasizing character development

Finally, falling action emphasizes a character’s development. The final moments of the story, after the protagonist has come to terms with their new truth, shapes the reader’s overall experience and understanding of the story. The aftermath of the protagonist’s climactic battle provides context for the story’s theme. The falling action shows the protagonist’s metaphorical “return home” while showing how they are now forever changed.

How will they handle this change?

How have these lessons altered them in some fundamental way?

The falling action answers these questions in order to add thematic depth and illustrate the protagonist’s final transformation.

Your secret weapon: Transformation exercises

Here are two powerful transformation exercises to help you create a dynamic and compelling resolution to your story.

✒️ Transformation Exercise #1

Make a list of three negative traits for your protagonist at the beginning of your story.

- Dishonest

- Corrupt

- Withdrawn

- Paranoid

- Naive

- Egotistical

- Selfish

- Negative

- Critical

- Distrustful

- Rude

- Immature

- Impatient

Next to these three words, write the opposite, positive quality.

Do you see where these positive qualities exist for your protagonist at the end of the story? Do you see how they delineate a powerful arc for your protagonist, and how your protagonist is a very different person at the end than at the beginning?

Remember that character suggests plot. By allowing your protagonist to embody these traits at the end of the story, situations will emerge to support their experience.

How can you make sure that you have written a compelling conclusion to your story?

✒️ Transformation Exercise #2

Take five minutes and ask yourself these two questions:

- How is my protagonist relating differently to other characters at the end than they were at the beginning?

- What do they understand at the end that they didn’t understand at the beginning?

Notice how the first part of exercise #2 creates a goldmine of images for what precedes your ending. In other words, this exercise will offer you potential scenes that are necessary to provide context for your ending. Rather than trying to “figure out” how to create a dynamic falling action, take a look at this exercise and notice how you can find create ways to dramatize your protagonist in this new place. With the second question, you will notice that this new understanding is going to inform your protagonist’s experience.

Need help shaping an ending that honors your climax, deepens character, and leaves your readers satisfied? Join one of my next workshops: The 90-Day Novel, Story Day Workshop, or The 30-Day Outline.