There’s no rhythm without some repeated notes. Certain literary and rhetorical devices are so ingrained in how we speak and think that we can forget that they’re there. That’s part of doing magic; hiding the seams and details so it really looks like a rabbit appeared out of a hat. One of those seams, in the world of literature, is parallelism: a literary device that acts as an umbrella for a few different techniques.

In this article, I will look at a few different forms of parallelism, examine their uses, and I’ll give you a Story Weapon to help explore parallelism in your own work.

Parallelism is a literary device that uses mirrored words or grammatical structures to create rhythm, balance, and emphasis in writing. By repeating patterns through techniques like chiasmus, anaphora, or epistrophe, this method makes ideas more memorable and draws the reader’s attention to what matters most.

Definition of parallelism

Parallelism is the use of words or grammatical structures that mirror each other to create a sense of rhythm and emphasize something about them.

You can think of parallelism as a broad concept that emphasizes balance and rhythm in writing. To help you pull some rabbits out of hats with this technique, let’s take a look at different types of parallelism.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

– Charles Dickens

Different types of parallel structure

Chiasmus and Antimetabole

One way to parallel grammatical structure is to mirror the first half of a sentence in the second. Such a mirror, split perfectly by a comma or conjunction, would be a chiasmus.

This literary device features an inverted structure — like an “ABBA” pattern. The words don’t have to exactly mirror each other to count as a chiasmus.

We can take some wisdom from Voltaire as an example: “The instinct of a man is to pursue everything that flies from him, and to fly from all that pursues him.” Though some tenses change —flies vs fly and pursue vs pursues — the structure is still inverted.

Or consider this truism: “Those who mind don’t matter, and those who matter don’t mind.”

A more specific type of chiasmus is the antimetabole, in which the words are perfect mirrors of each other. Chiasmus and antimetabole have a rectangle and square relationship; all antimetaboles are chiasmi (because they rely on an inverted structure) but not all chiasmi are antimetaboles (because they don’t always use the same words).

An antimetabole you might be familiar with is “All for one, and one for all.” It pops up originally (at least in our record of genealogy) in Shakespeare’s poem “The Rape of Lucrece” as: “That one for all, or all for one we gage.” It was later popularized by Alexander Dumas in The Three Musketeers.

You might’ve also heard: “When the going gets tough, the tough get going” or “I mean what I say and I say what I mean.” And every American has heard, at some point, this line from President Kennedy’s inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

Why are antimetaboles and chiasmi popular forms of parallelism?

- The repetition helps them stick in your memory.

- The parallel structure helps emphasise a point.

In “When the going gets tough, the tough get going,” there are only five unique words in that sentence. It communicates an idea and flows easily off the tongue.

Let’s take a more contemporary example from the popular anime Jujutsu Kaisen. One of the antagonists poses this question to Satoru Gojo, the most powerful sorcerer of his time: “Are you the strongest because you’re Satoru Gojo? Or are you Satoru Gojo because you’re the strongest?”

This use of chiasmus points to a fascinating question of causality, posed similarly in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical Cinderella (1957): “Do I love you because you’re beautiful, or are you beautiful because I love you?”

Anaphora and Epistrophe

Another way to create parallel structure is to repeat certain words, even as the phrases in the sentences change. If you repeat words at the beginning of successive clauses, you’re using anaphora.

It helps create rhythm, making the sentence pleasing to the ears. It’s the reason this line from Casablanca is so iconic: “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.” The repeated words here are “all the,” slowly zooming out from the gin joint, to the town, to the whole world.

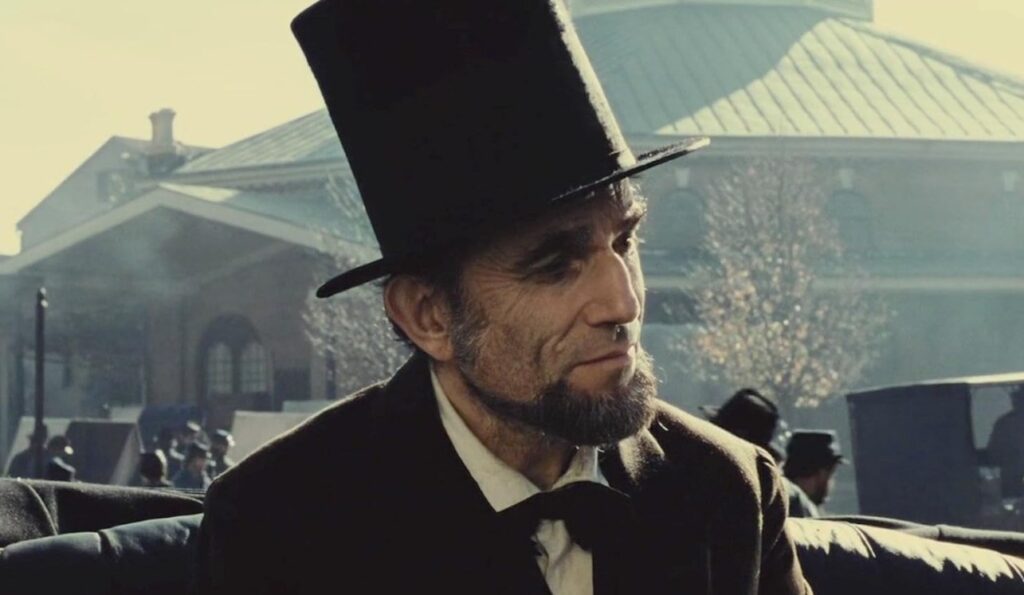

Orators use anaphora for emphasis, like President Lincoln in his address at Gettysburg: “But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground.”

The repetition of “we can not” underscores the importance of the sentence in the company of other sentences that don’t use anaphora and repeats the idea with different similes: dedicate, consecrate, and hallow.

The sibling of anaphora is epistrophe, in which words are repeated at the end of successive phrases.

Let’s start with another line from Lincoln, at the end of the same speech, in which he promises that a “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

By repeating the phrase “the people” at the end of each phrase, the ideas he’s putting forth are underscored. It presents, succinctly, a core idea of American democracy.

Epistrophe appears on the page in Portrait of the Artist as Young Man by James Joyce:

“He would never swing the thurible before the tabernacle in God’s house, He would never carry the monstrance in procession in God’s house, He would never serve mass again in God’s house.”

This is actually both anaphora and epistrophe, with the phrases “he would” and “God’s house” repeated.

Your story weapon: Advice on parallelism

Parallelism communicates a simple rule of writing, one you’ve likely already` grasped from intuition. When we put similar words and sounds together, it focuses attention on the ideas represented by those words.

Part of the reason there’s more attention there is because parallel structures are pleasing to the ear and to the tongue. When you come upon a part of your dialogue or storytelling that you want the reader to focus on, parallelism can be your best friend. The way you choose to apply that is up to you, and there are many literary devices that’ll do the job slightly differently.

The best way to go about this is to let your pen flow as best you can without getting too caught up in trying to shoehorn parallelism into the equation. When you revisit a text, you’ll have a better idea of which parts you want to emphasize to the reader. That’s your chance to try out some different types of parallelism and practice these literary devices. Once you get in the habit of doing so, it’ll become second nature to you.

To the speech writers and playwrights of the world, parallelism often shows up in their first drafts and might actually need to be taken out in an edit sometimes if the use of these devices has become too habitual. Repeatedly using repetition too much can turn into cliché. Be intentional about what you emphasize and enjoy the process of crafting a great sentence!

Parallelism is easiest to master when you hear it, feel it, and revise with intention. Explore this tool and more literary devices in one of my next workshops: The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, Story Day