What is a story without a plot? Not much! A plot is the sequence of events that helps give a story its narrative shape, momentum, and purpose.

While a story is the full tapestry of characters, themes, and ideas, the plot is the series of events that guides your reader from beginning to end. In this article, I’ll look at the purpose of plot, go over its stages and different types with some examples, and finally offer you a Story Weapon to ensure that you always put the aliveness of your characters ahead of your idea of what happens.

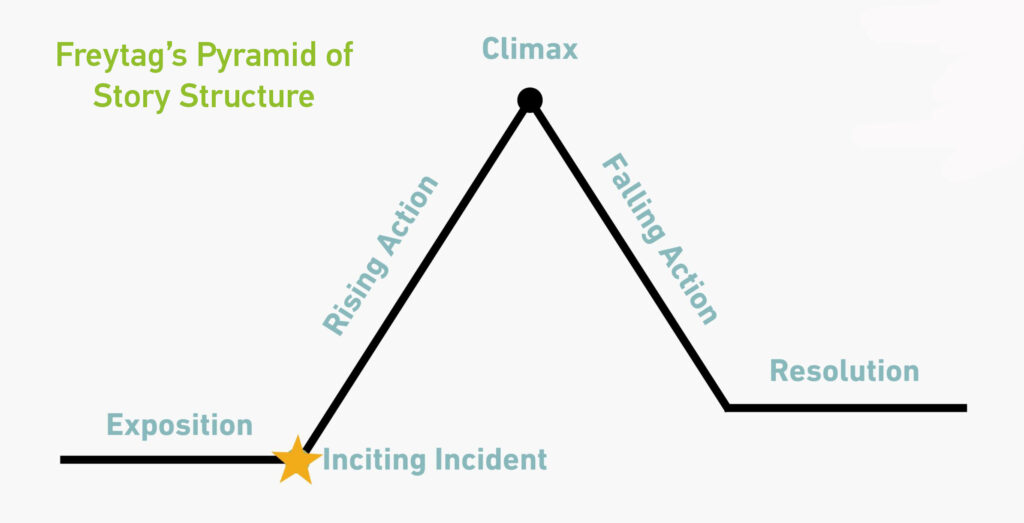

Plot is the structured sequence of events that gives a story momentum and shape, guiding readers from beginning to end through conflict and resolution. While structure models like Freytag’s Pyramid and common plot types are useful, the strongest plots ultimately grow out of character choices and instincts rather than rigid ideas about what “should” happen.

The definition of plot

According to Aristotle’s Poetics, a plot is the structured arrangement of events consisting of three parts: the beginning, middle, and finally, the end.

Later, in the 19th century, a German novelist, Gustav Freytag, expanded upon this format and added additional components and terms: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

Plot vs story

Let’s take a moment to debunk the myth that plot and story are the same: a plot is only a piece of a story.

A story is a complete narrative that contains the plot, alongside other literary devices and themes. Plus, you might not have a single plot, but several subplots that progress simultaneously across the points of view of different characters.

The overall story will give your reader a picture of the work, complete with themes, character development, and ideas. A plot conveys how the story progresses through cause and effect, and can be used in a linear or non-linear fashion.

“Plot is people. Human emotions and desires founded on the realities of life, working at cross purposes, getting hotter and fiercer as they strike against each other until finally there’s an explosion—that’s Plot.”

– Leigh Brackett

The purpose of plot in storytelling

Considering how essential it is in storytelling, let’s examine what role a plot serves in a story.

- Organizes the story: It can sometimes be difficult to develop multiple characters and juggle different story elements at the same time. A plot provides a framework to structure your story in a chronological way.

- Drives conflict: The plot drives and escalates conflict as the story progresses, raising the stakes and keeping the readers on their toes.

- Creates tension: An elaborate plot can create tension between characters and factions, build a sense of anticipation and uncertainty that can help convey a strong message, develop characters, and set up a strong resolution.

- Engages audience: A plot gives your readers something to care about and someone to root for. When a story has a well-developed plot with interesting characters, your audience will have no choice but to stick around till the end.

- Delivers a satisfying conclusion: Everything that happens in your plot should be driving your protagonist inexorably towards a satisfying conclusion. The more a plot invests in its ending, the more satisfying and cathartic the experience will be for your reader.

5 stages of plot in Freytag’s Pyramid

We briefly talked about Aristotle and his basic plot structure. Now, let’s go over Freytag’s Pyramid and how this structural model expanded on the building blocks of story.

By following these 5 stages, or similar models, you can track how your plot flows logically, maintains momentum, and creates a cohesive emotional arc for your readers.

1. Exposition

The plot starts with exposition, where the reader or viewer is introduced to the necessary background information. This typically involves meeting characters, establishing their relationships, understanding the setting, and other relevant details.

Example: The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

The opening pages explain the structure of Panem, the annual reaping, and Katniss’s family situation, grounding the reader in the political system and social stakes before the plot accelerates. This exposition establishes the world’s rules and tensions while remaining tightly focused on Katniss’s lived experience.

2. Rising Action

The rising action is an incident that kick-starts the conflict for the characters. It sets in motion a series of events that slowly unfold over the course of the story and include significant plot points.

Example: Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

Catherine Morland’s imagination and fascination with gothic novels lead her to suspect dark secrets. Her growing curiosity, combined with her interactions with the Tilneys and the mysterious setting of the Abbey, heightens the tension and anticipation.

3. Climax

After the rising action comes the climax, which is often the pivotal turning point of the plot. The previous elements all lead up to this, and it is here that the central conflict comes down with full force.

Example: The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

The climax occurs when Amir returns to Kabul and confronts Assef to rescue Sohrab, Hassan’s son. This confrontation is intensely physical and emotionally charged, forcing Amir to face the guilt and cowardice that have haunted him since his childhood. The outcome of this fight determines both Sohrab’s fate and Amir’s chance at redemption, marking the turning point of the story.

4. Falling Action

After the climax, the tension dies down a bit, and this is called the falling action. These include the series of events after the climax, and often set the stage for the final resolution. In most stories, this is where the conflict slowly decelerates to prepare for the end and allows the audience to fully process the climax.

Example: It by Stephen King

The town of Derry begins to return to normal, though the trauma of past events lingers. The members of the Losers’ Club begin to go their separate ways, realizing that their bond, forged in childhood, will fade as they return to their adult lives.

5. Resolution

The resolution or denouement is the final part of the plot. It ties up the loose ends and reveals the consequences of the events in the story, as well as showing the fate of the characters. In serial titles, the resolution also teases the next installment.

Example: The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

Didion comes to a quiet acceptance of her husband John’s death and the fragility of life, recognizing the impossibility of reversing loss despite her wishes and rituals. She reflects on the year of grief she has endured, acknowledging both the intensity of her mourning and the resilience required to continue living.

7 Types of Plots

In his book The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker outlined some archetypal categories of plots often found in stories. It should be noted, these are not all encompassing. Just as the Hero’s Journey story structure model should only be used as a source of inspiration and not a strict template, the plots described below should not be considered a mold to fit into but merely a reference to popular story types.

- Overcoming the monster – This plot structure involves a protagonist who sets out to defeat an antagonist that threatens them, their home, or their family. It is a very basic, but effective plot type that is typically found in classical and medieval literature. (Examples: Beowulf, tales of Theseus, and Perseus)

- Rags-to-riches – This is an aspirational plot type in which a protagonist acquires wealth, power, and status over the course of the story. Along the journey, they evolve and grow, often realizing something quite surprising. (Examples: Aladdin, Cinderella, and The Pursuit of Happyness)

- The quest – Here, the protagonist sets out on an adventure, often with companions, to retrieve an object or reach a particular location of significant value. They often face hazardous challenges and obstacles along the way, but persevere because the stakes are often quite high in these types of plots. (Examples: The Lord of the Rings, The Divine Comedy, The Aeneid, and Raiders of the Lost Ark).

- Voyage and return – The protagonist ventures to a strange new place, overcomes threats, and tries to find their way back. This plot is similar to the quest, but rather than a journey towards something, the focus is often on the journey back home and how the characters return with their newfound experience. (Examples: The Odyssey, Gulliver’s Travels, Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and The Hobbit)

- Comedy – This is a light and humorous plot that thrives on hilarity and adverse circumstances. (Examples: Much Ado About Nothing, Superbad, and Good Omens)

- Tragedy – A tragedy involves a hero with a major flaw that ultimately becomes their undoing. (Examples: Oedipus Rex, Romeo and Juliet, and The Great Gatsby)

- Rebirth – This plot centers around the redemption of a protagonist who changes their ways and becomes a better person as a result of events in the story. (Examples: Iron Man, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and A Christmas Carol)

Your story weapon: Character suggests plot

The goal in creating a compelling plot is to marry the wildness of your imagination to the rigor of story structure. When you place your focus squarely on the plot while paying lip service to your characters, your theme gets lost. Remember that character suggests plot. Only by trusting your instincts and allowing your characters to surprise you can you arrive at a satisfying plot.

You must not confuse your instincts with your ideas. Your instincts will lead you to a deeper truth, while your ideas, if you don’t hold them loosely, will squeeze your story into a box. Because the truth is that your idea of your plot is never the whole story. As you inquire into the world of your story, you will discover that in being willing to shed your fixed idea of what you think should happen, the truth of your story will emerge.

If you’re ready to write a story that feels alive, surprising, and inevitable, join one of my workshops to explore how character, instinct, and structure can work together on the page: The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, Story Day