Stories become richer when they wink at the world beyond their pages, and that’s exactly what an allusion does. By dropping hints to myths, history, literature, or even pop culture, writers let readers make the connection themselves. It’s a clever way to give your story depth, spark recognition, and layer meaning without spelling everything out.

In this article, I’ll go over what an allusion is, how we use them naturally in conversation, give some examples of allusions and show you how to use them in your own work.

An allusion is a subtle reference to a well-known story, event, or figure that adds depth and meaning by relying on the reader or viewer’s shared cultural knowledge. They can enrich your story’s texture, invite interpretation, and connect your work to a broader literary or historical conversation without spelling everything out.

Definition of allusion

An allusion is a literary device that subtly points to a generally known idea, event, or work. By pulling from a shared pool of cultural or literary knowledge, an allusion places something familiar into a new context.

Allusions rely on the audience to catch the reference; they don’t spell it out. Your readers are left to make the connection themselves, or to turn to a search engine if they don’t know what it means. For example, if someone calls a brilliant but reckless idea “opening Pandora’s box,” they’re assuming others know the Greek myth well enough to understand it signals unleashing a lot of trouble.

Examples of allusion in our everyday speech

We all use allusion in our common parlance; sometimes it’s the best way to make your point understood. Not for nothing, it’s fun to speak with color!

Let’s say you’re thinking of suing a huge corporation, a “Goliath.” This brings to mind, mostly to those fluent in Western culture, the image of David as a humble shepherd boy trying to take down the giant warrior Goliath from biblical stories.

We do the same when we call a task herculean or suggest that there’s been a renaissance in your creative life.

You might call a pursuit quixotic or Sisyphean.

A person might be referred to as a Sherlock Holmes or an Aphrodite. God forbid, they could even be a Benedict Arnold! Whether a particular allusion is religious, mythological, or literary, these references connect us to the broader world.

“A little bit of one story joins onto an idea from another, and hey presto, . . . not old tales but new ones. Nothing comes from nothing.”

– Salman Rushdie

Allusions in a “historical” context

When deciding if it’s appropriate for your characters to make these casual allusions, it’s helpful to define the limits of your world. Do your characters exist in the world we do, where these figures and moments exist in shared memory?

If your story takes place in the past or the future, that would change the type of reference they make. For example, there’s a twenty-year period in history when World War I was called the Great War. People might’ve looked at you funny if you called it World War I.

This is also a great opportunity to get creative; if your plot takes place in the future, what events could your characters reference?

Just as we make allusions to real world events and history all the time, your characters might do the same. It’s a great way to link us to the world of your story. After all, how else can your characters make sense of a new war, or a new celebrity, or a new messiah in their world? Only by comparing it to the last one in their shared memory.

Here’s a sci-fi example from The Dune Encyclopedia by Willis E. McNelly, a companion piece to Frank Herbert’s Dune series with the fictional allusions in bold:

The practice of maintaining stockpiles of atomic weapons as an integral part of a House’s defenses began when primitive nuclear weapons were invented on Old Terra on the eve of the Little Diaspora, by the ‘Raw Mentat,’ Einstein, who was working for House Washington. When Einstein succeeded in his attempts to construct these weapons, two of the first were used to settle a trade dispute with House Nippon . . . Possession of the Empire’s only atomic weapons gave House Washington the prestige and power it needed to displace House Windsor.

Even the way these events are remembered or referenced tells us something about the present world. To refer to the Japanese empire, the United States, and Great Britain as House Nippon, House Washington, and House Windsor is to tell us something about how the modern world in Dune considers governments. It fleshes out the idea of a Mentat by alluding to a figure we know: Einstein. It even brings new questions to our minds; what is New Terra and what was the Big Diaspora?

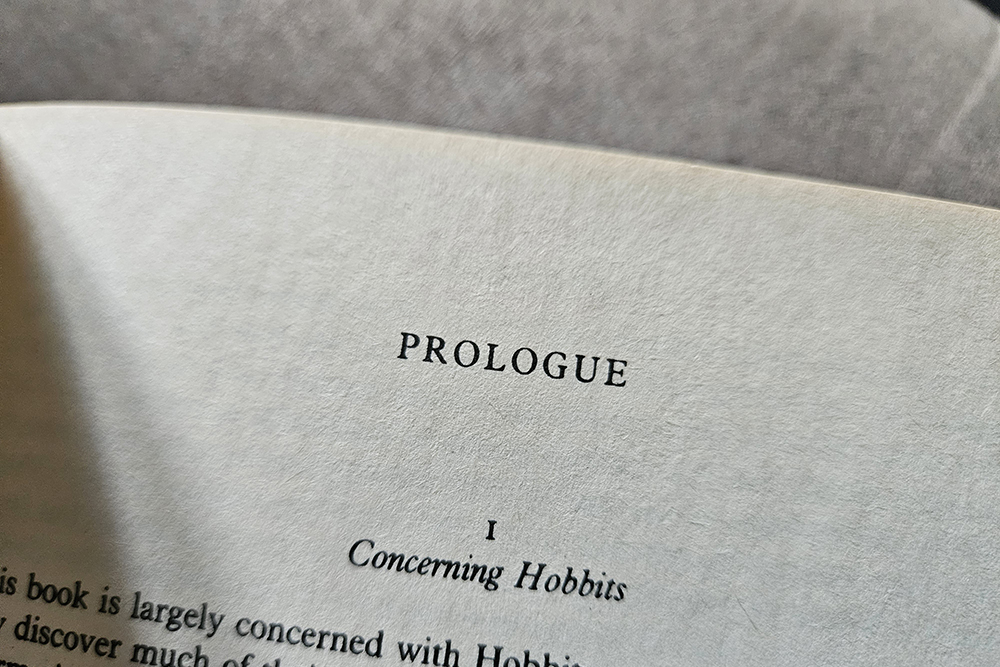

Allusions in literary titles

This can be a great way to introduce the texture of your tale before people even open the book or watch the movie trailer. Your reader enters the world of your story with an image already in mind.

Here are some examples of allusions in literary titles:

- East of Eden by John Steinbeck alludes to the story of Cain and Abel, which is explored at great length in the text. In fact, the whole book is an allegory (link to blog). The full quote is: “So Cain left the Lord’s presence and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden.”

- The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner references the Bard himself, specifically Act 5 Scene 5 of Macbeth. Macbeth bemoans the curse of living in this monologue, which ends with: “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more. It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” The seeming futility of life is explored in the text by Faulkner. Furthermore, in the era where the book takes place, a mentally handicapped person was called (quite cruelly) an “idiot.” Part of the book’s narration is from the perspective of Benjy, who suffers from a mental handicap. His part of the story is the “tale told by an idiot.”

- For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway alludes to a poem by John Donne, who was deathly ill at the time he wrote it. Donne spoke of the practice of funeral tolling — ringing a bell when someone died — and commented: “I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” Hemingway uses this allusion to hint at the ending of his novel: the bell tolls for the protagonist.

- A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole takes its title from an essay by Jonathan Swift where this line appears also as the epigraph [link to blog]: “When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him.” The book’s protagonist is a self-declared genius, allowing the readers to entertain who the dunces are: the other characters or the readers themselves?

Whether you’re pointing back to imaginary or real events, or fictional or historical people, an allusion is a great way to connect your work to another great artist while ensuring that the reference is in service of your story.

If you would like to deepen your understanding of allusion and other essential literary devices, join one of my workshops: The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, Story Day.