I suppose everything is easier said than done. The same is true for writing. It’s one thing to say a person is sad, it’s another to dramatize a character drowning in sorrow and submerge your reader in the same aching pain. The art of showing takes skill.

The adage “show, don’t tell” is a method to ensure that your story isn’t merely an account of what happened, but a portal into the experience. It’s the difference between hearing about a great baseball game and standing at the pitcher’s mound. In this article, I will discuss how to take your reader into the character’s experience, then we will explore examples of showing vs telling, and finally, I will offer you a story weapon to help you bring your narrative to life.

“Show, don’t tell” means immersing readers in your character’s lived experience rather than stating emotions outright. Use action, thought, and subtext to invite interpretation. Let your readers feel the deeper meaning for themselves while making your stories more vivid and resonant.

Take us into the experience

Perhaps you have an idea of what happens in your story; there may be a version that plays out in your imagination, but when you try to commit it to paper you feel stuck. You can see the way the characters move and speak and dress, but for some reason the story just doesn’t feel like it is animated from within.

The challenge of sharing your story with the world is that you’re sketching your story on a canvas that doesn’t belong to you: the canvas of someone else’s imagination. They see your characters with different faces and clothes; they imagine different textures and colors in the tapestry, but the fundamentals of the story must be universally relatable.

The art of showing involves the art of being connected to the character’s inner life. Everything else is window dressing. The thing that makes your story universal is that it connects your readers to an experience that everyone can relate to.

Here are two quick examples:

“She stood up, her hand over her heart, and stood still as if she had been turned to stone.”

– To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Rather than stating that the character is shocked or distressed, the physical stillness and gesture communicate her emotion organically.

“He was comfortable but suffering, although he did not know it, since he was not one to think about pain.”

– The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

Instead of simply telling us “the old man was in pain,” Hemingway shows it through contradiction and restraint. The sentence reveals endurance, denial, and character all at once — letting the reader feel the suffering rather than being instructed to notice it.

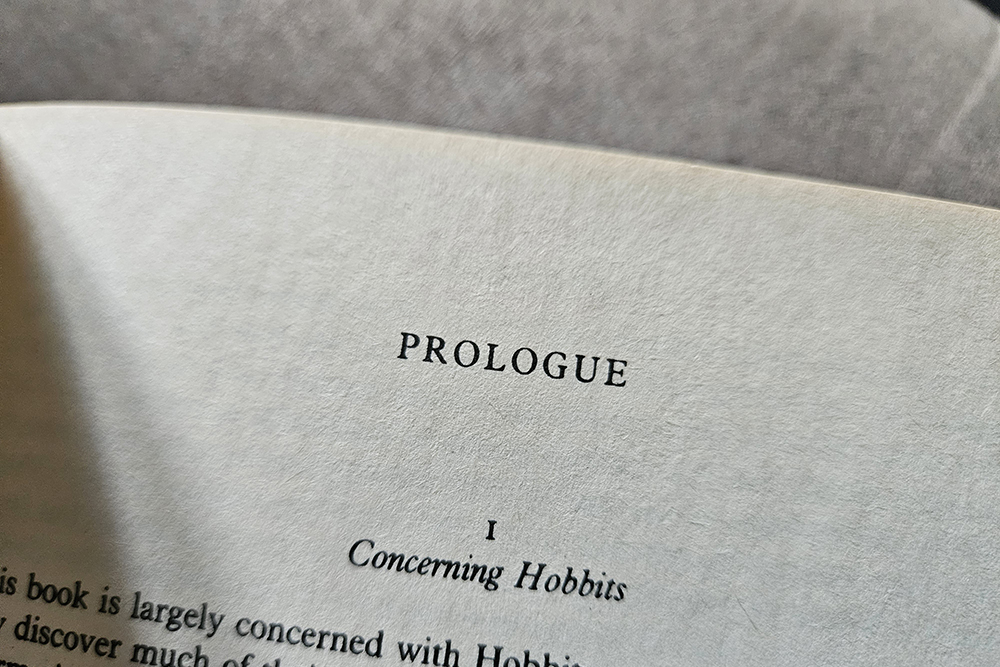

The iceberg theory

To better understand what it means to suggest and not state in this way, let’s turn to Ernest Hemingway again and look at his “iceberg theory”:

If a writer of prose knows enough of what [they are] writing about [they] may omit things that [they know] and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.

The difference between telling the story and showing it is how you communicate to the reader that this iceberg exists.

You have the full thing in your head; you could (relatively) easily draw the whole thing. This is where the ice forms, this is where it meets the water, this is the iceberg. Hemingway’s point here is that there is a better way to communicate. While you do have to imagine the whole iceberg, you need only describe the eighth of it that lies above water.

The reader will get a sense that there is much more there as their subconscious mind stitches together the rest of the iceberg. This allows for the story to change every time they encounter it and glean more meaning from it. (And it gives them a reason to discuss it with their friends!)

“There’s an old adage in writing: ‘Don’t tell, but show.’ Writing is not psychology. We do not talk ‘about’ feelings. Instead the writer feels and through her words awakens those feelings in the reader. The writer takes the reader’s hand and guides him through the valley of sorrow and joy without ever having to mention those words.”

– Natalie Goldberg

How to lay the clues

So how do you actually make this happen? There’s a way to lay clues for your reader to draw conclusions about the story, instead of spoiling the mystery.

One way to approach this is to think of each scene as a line of information that you want to get across to the audience. There may be more going on just one thing, but let’s focus on one for the time being. Say, for example, you have a moment when one character is trying to ascertain the truth about something from another. We can set the intent of this scene as the subtext, instead of the text.

In this first example, we’ll tell the reader what’s happening instead of showing them:

Samantha did her best to keep her gaze firm and her breaths even. She didn’t want to be caught. It was hard to tell if the ruse was working, but Terry didn’t seem particularly suspicious. They spoke about the missing treasure for a few minutes and Terry seemed satisfied. That was the end of it, at least for now.

This is almost like giving scene directions instead of the scene itself. There’s information here that we need for the story to continue, but it hardly puts us in Samantha’s shoes or Terry’s. Instead, it’s more like we’re getting a detailed report of that moment.

Let’s see if we can show what’s happening here and change the feeling.

In . . . out . . . hold. In . . . out . . . hold.

These were the only thoughts in Samantha’s mind as she spoke to Terry. She had learned long ago that an anxious mind is less useful than focusing just on her breath. If this was a lie detector test, she would fail anyway.

Terry absentmindedly mused about the missing treasure and she chimed in, matching his tone. Everyone likes to hear their perspective mirrored back with approval. Terry was no different. A few moments of stroking his ego, and that was it. At least for now.

This is a more active version of the same scene. By focusing on showing and not telling, we avoid the mistake of stating the emotions that Samantha feels and telling the reader what they should get from the passage. This gives us a sense of interiority, something the first example fails to do. We’re burrowed deep in the experience Samantha is having and we’re much more alive to the story.

Your story weapon: An experience is not a feeling

Don’t confuse feelings with experiences. If you tell us what a character is experiencing, it will be meaningless. But if you dramatize it, then it could be enormously impactful.

Frankly, your reader doesn’t much care what a character is feeling, but they might deeply care what a character is experiencing. Feelings are transient — they’re like the weather channel. They pass. They don’t mean much. Experiences are different, as they can contain a whole host of feelings that may even contradict each other. By showing, you are dramatizing the character’s experience, thus allowing your reader to have their own.

As you practice the art of showing and not telling, let your characters’ actions and thoughts be in service to the inner experience at the heart of your scene.

After a while, the habit will be a part of your method and you won’t have to keep the adage “show, don’t tell” at the forefront of your mind. The more you experiment with it, the more vividly your readers will live inside your story, discovering its depths on their own.

If you’re ready to move beyond explanation and learn how to immerse readers more fully, join one of my workshops and practice turning scenes into moments your audience can feel: The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, Story Day