Crafting a compelling story comes with several responsibilities. You are in charge of creating the plot, the characters, the prose, the dialogue, and, last, but not least, the world in which the story takes place.

Many great works of literature make use of the setting we’ve been given: the natural world. Other writers opt to create their own. If you’re interested in being in that latter group, this article is for you. I’ll discuss what worldbuilding is, go over different methods, and how much detail is necessary to flesh out a convincing setting. Finally, I’ll give you a Story Weapon to help choose the right worldbuilding method for your story.

Worldbuilding is the process of creating a fictional setting that supports your story, ranging from loosely implied, dreamlike worlds to rigorously planned systems with defined rules. By choosing the approach that suits your imagination and serves your characters, you ensure the world you’re crafting enriches the story rather than overwhelming it.

Definition of worldbuilding

Worldbuilding is the art of creating a fictional setting for the purpose of telling a story.

The borders of this place stretch as far as you’re willing to imagine. It could be as small as a village, or it could encompass countries, a whole planet, or the expanse of an imaginary universe. Even if your worldbuilding spreads through galaxies, your story might still just take place in a single town within that universe.

Deciding how much detail you’d like to include in your world is a creative choice. Given that you won’t be the first to do some worldbuilding, let’s take a look at some different approaches to the craft.

“This tremendous world I have inside of me. How to free myself, and this world, without tearing myself to pieces. And rather tear myself to a thousand pieces than be buried with this world within me.”

– Franz Kafka

Soft Worldbuilding

The simplest form of worldbuilding is “soft worldbuilding.” This is a creative style that invites the reader to imagine the links between fantastical elements in the fictional world, rather than telling the reader all the ins and outs of how that world works.

Some great examples of this can be found in the work of Hayao Miyazaki, co-founder of Studio Ghibli and director of movies like Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke. These stories take place in both high fantasy and low fantasy settings, full of magical occurrences in magical places.

Despite the fact that many of these places are alien to the audience, Miyazaki chooses to leave us in the dark about the rules of the world. Instead, we are left to watch the characters navigate landscapes with bizarre characters and make our own assumptions about how things work.

This creates a more dreamlike fantasy setting, where images and ideas float between writer and reader freely. It allows storytelling to be more than a dictation of rules for different settings. Rather than explaining the internal logic of the world to your audience, you invite them to the table. They’re allowed and encouraged to use their own imagination about the spirits and monsters they see, using the clues you’ve left them.

Part of the advantage of soft worldbuilding is that you get to keep making decisions as your draft unfolds. Without a strict set of rules you’d need to follow, your setting can gradually change and grow as different needs arise in your story. You’re free to keep imagining what could possibly show up next.

That said, you’ll still have to review the things you made up to make sure there’s some consistency. After all, you can’t have implied in chapter 10 that magic is banned in human society and then mention a government program to teach magic in chapter 17. If you’re embarking in some soft worldbuilding, try keeping a running list of the details you’ve added as your draft unfolds.

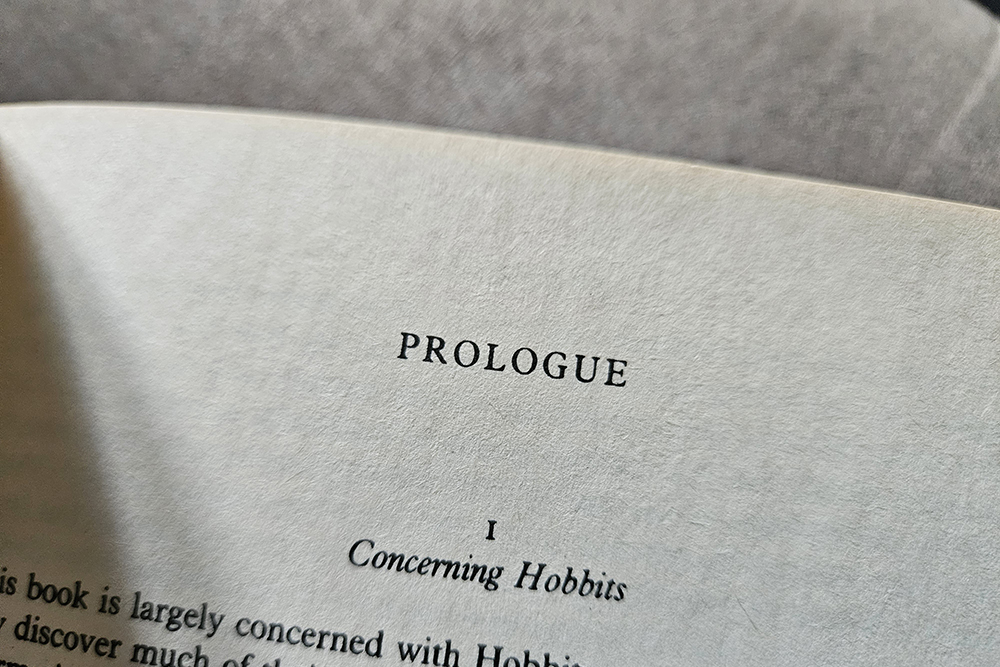

Hard Worldbuilding

This is the style preferred by writers like J.R.R Tolkien and George R.R. Martin. Even if you don’t have the “R.R.” initials in your name, you can still try your hand in some hard worldbuilding.

This approach to the craft is characterized by mapping out certain rules and conditions that govern your world before you start writing. The extent of that is totally up to you.

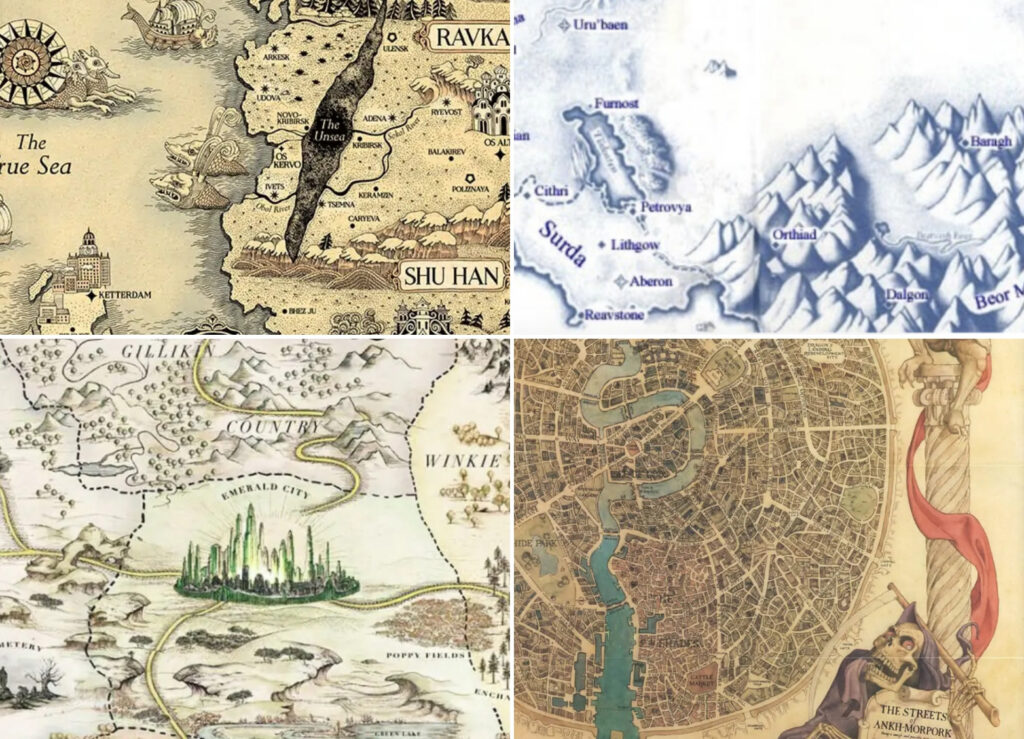

It might look like drawing a rough map of the different regions in your imagined world, describing the ecological landscape, creating specific technologies or magic systems, or even crafting fictional languages.

This is a great choice if you have a taste for anthropology. You get to write a miniature encyclopedia of your own.

The advantages and disadvantages of hard worldbuilding mirror those of soft worldbuilding.

You run less of a risk of some internal contradiction in the logic of the world since you’ll have guidelines for what is possible as you’re planning things out. The work you do before writing the rough draft provides the context and offers many ways your characters can engage with the broader setting.

All of the details you imagine may not make it into the story, at least not overtly, but that doesn’t mean your work is wasted. Your reader often senses that there’s more depth to the world than the facts that they’ve been given.

The disadvantage of hard worldbuilding is that there’s no limit to the number of things you can make up. You have to stop yourself at some point. Finding the balance and deciding when you’ve done enough to get started on the writing part can be tough.

“Nobody believes me when I say that my long book is an attempt to create a world in which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real. But it is true.”

– J. R. R. Tolkien

Top-Down vs Bottom-Up

When it comes to hard worldbuilding, there are generally two approaches.

The top-down approach

You can think of this style as shrinking the focus of your worldbuilding until it reaches the immediate setting of the story. The first thing you do is make all the big decisions, many of which are greater in scope than the minute details that’ll actually show up in the story. This includes questions such as “How many continents are in this world?” or “How long do the different species on this planet live?”

Just as the miniature stories of our lives are defined by premises like the length of our lives and how long it takes to travel to another place, so too are the ambitions of your characters defined by these big questions. After all, a quest or love affair has a different meaning for a character who lives a thousand years.

The bottom-up approach

This means that you begin with your story and, when a question appears for a specific, more detailed element, you do a bit of worldbuilding to answer it. This is still different from soft worldbuilding, which focuses on maintaining a flexible atmosphere with intentionally vague rules as you go along.

Say, for example, your characters are in need of a vessel and are trying to buy it. That might make you wonder about the currency in this fictional place, and you get to set a monetary system in place. Then you can continue to write until the next question appears. You could also think of this as inside-out worldbuilding as opposed to outside-in worldbuilding.

This might be the right choice for you if you want a balance between writing and worldbuilding; sometimes researching how currencies are created can be the break you need from that blank page.

Terry Pratchett, one of the best worldbuilders out there, was a fan of this approach. Here’s what he had to say about it:

“You had to start wondering how the fresh water got in and the sewage got out . . . World building from the bottom up, to use a happy phrase, is more fruitful than world building from top-down.”

It’s important to note that while bottom-up worldbuilding involves less preparation at the outset, it also places subtle limits on what you can plausibly imagine. When you begin writing and invent details only as they become necessary, you tend to default to familiar assumptions — physics, social norms, language, and time structures that closely resemble our own. This approach leaves little room to question or reinvent the foundational rules of the world itself.

What if the characters don’t speak like we do, but communicate telepathically or with hand signals? What if days last two weeks and then it’s night for forty minutes? What if people get married in their late seventies because it doubles their lifespan? These concepts may sound a bit ridiculous, but exploring bold possibilities before you start drafting can open new creative pathways.

Your story weapon: Finding your method

How do you decide between these approaches to worldbuilding? How do you know if you want your worldbuilding to be soft, hard, bottom-up, or top-down? As always, go with your gut. You know already if the thought of creating imaginary laws and species is intimidating to you or exciting. You can let your curiosity guide you through the process.

There are no hard and fast rules, just guidelines to assist you in your work. You can use these methods to ensure there is internal consistency in your world, which is necessary for your setting to be convincing. One of the joys of reading is being transported to a new reality and finding new depths to explore through or alongside the characters.

Brevity and focusing on your characters goes a long way in worldbuilding. Whether you do a lot of research or very little, keeping your reader’s attention largely depends on your ability to make them care for your characters.

There are too many details in our real world for us to remember; you’ll have to forgive your readers if they have less enthusiasm for the economic policy of your fairy kingdom than you do. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t come up with it! It just means that it should exist in service of the story, not the other way around.

I’ll leave you with the words of J.R.R. Tolkien from his lecture “On Fairy-Stories” written in 1938:

For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it. So upon logic was founded the nonsense that displays itself in the tales and rhymes of Lewis Carroll. If men really could not distinguish between frogs and men, fairy-stories about frog-kings would not have arisen.

Make your story’s world come to life in my next 90-Day Novel workshop, where you’ll develop a setting that is coherent, evocative, and inseparable from your story’s central conflict.