Understanding when and how to use active vs passive voice isn’t just a matter of grammar; it’s a matter of storytelling. The active voice propels readers forward with clarity and energy, while the passive voice can obscure, highlight, or shift focus in ways that enriches the narrative depth.

Writing is as much about choice as it is about expression: do we act, or are we acted upon?

Much of what we’ve been taught about writing emphasizes the active voice, celebrating sentences where the subject drives the action. Yet, in the shadow of that rule lies the often-overlooked passive voice. This is a literary tool with unique power, capable of shaping tone, emphasizing perspective, and even revealing subtle truths about our characters or the world they inhabit.

In this article, I’ll explore the mechanics of both voices and uncover the strategic moments when passivity can become your strongest tool. Finally, I’ll give you a Story Weapon to master the balance between them.

Active voice drives clarity, momentum, and agency in storytelling, while passive voice can deliberately shift focus, obscure responsibility, or reflect a character’s loss of control. Used intentionally, balancing the two allows writers to mirror emotional states, power dynamics, and perspective, deepening the narrative’s texture and meaning.

Active and Passive voices defined

The active voice is a sentence structure in which the subject of the sentence takes the action of the verb.

An easy example is “Delilah drove the car.” Delilah is the subject, the car is the object, and she is actively driving it.

The passive voice is the inverse where the subject of the sentence receives the action.

That would be “The car was driven by Delilah.” Though the information presented is the same, the latter case has the car as the subject, Delilah as the object, and the car is passively being driven.

When to use passive voice

“The traveler was active; he went strenuously in search of people, of adventure, of experience. The tourist is passive; he expects interesting things to happen to him. He goes ‘sight-seeing.’”

– Daniel J. Boorstin

At some point when you learned how to write, a teacher probably told you to always choose the active voice. Your teacher wasn’t wrong; nearly everything we read is formulated in the active voice these days. Even Search Engine Optmization (SEO) tools online are geared to favor active voice over the passive.

So, when would you ever use the passive voice?

Propaganda

One way you can use the passive voice is to obscure information or remove blame. It removes the volition involved in an active choice.

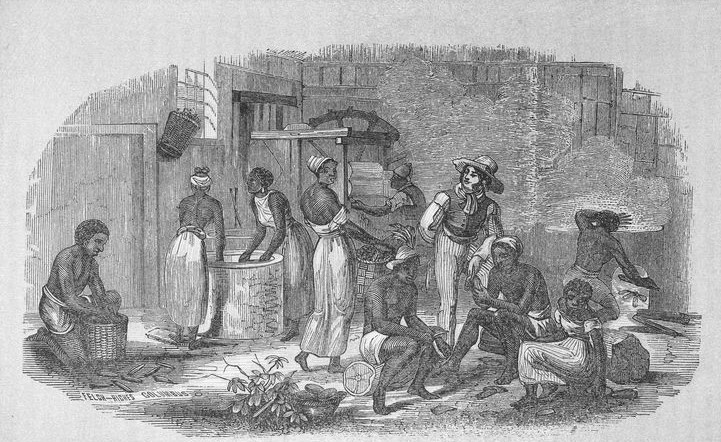

A particularly relevant example of this appeared back in 2015, when textbooks in Texas were found to use the passive voice in discussing the issue of slavery. This is analyzed beautifully by Ellen Rockmore, who was a professor of writing and rhetoric at Dartmouth College at the time and later became a member of the New Hampshire House of Representatives.

‘Families were often broken apart when a family member was sold to another owner.’

Note the use of the passive voice in the verbs ‘were broken apart’ and ‘was sold.’ If the sentence had been written according to the principles of good draftsmanship, it would have looked like this: Slave owners often broke slave families apart by selling a family member to another owner. A bit more powerful, no? Through grammatical manipulation, the textbook authors obscure the role of slave owners in the institution of slavery.

This tone of voice suggests a certain inevitability to what happens. If you’re writing for a character or a narrator who may use propaganda, the passive voice is a great tool to differentiate their voice from the other parts of your story. By removing volition from the actors in a situation, your propagandist might be able to smooth over the rougher, more corrupt actions of some characters.

If the shoe fits

There are also times when passivity is a part of the subject matter and the passive voice is appropriate. Let’s lean on another piece of analysis from a professor of writing, this time from Constance Hale. In this passage from Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, the passive voice is particularly helpful:

‘The married woman’s significance can only be conferred by the presence of a man at her side, a man upon whom she absolutely depends. In return for renouncing, collaborating, adapting, identifying, she is caressed, desired, handled, influenced.’

Greer underscored her point—that marriage saps a woman’s power, requiring her to trade active engagement for passively standing by—by putting those final verbs into the passive voice. By using the passive voice in the first sentence, Greer also kept our focus on the married woman, the most important part of her passage, instead of the presence of the man by her side.

In the previous example, the suggested passivity of the slaveholders was an attempt to obscure or lighten an evil of history. Here, the passivity of the married woman is a core part of the experience and Greer’s argument.

In Greer’s framing, the woman has no choice but to be acted upon. It’s a creative choice for the man to be invisible, as the force of patriarchy often evades notice. In both cases, the writer chose to suggest passivity by using the passive voice.

Narration

When choosing if active or passive voice is appropriate, you might ask yourself how your character feels. Do they feel like an actor in their surroundings or do they feel like a victim? Are they right?

There are times in life when we feel quite active. We may have made a conscious decision. We chose to leave a job and get a new one, or we chose to try a different brand of cereal.

Other times, life seems to take control over us. We don’t choose to fall in love, love sweeps us off our feet. Rarely do we choose to die; it’s much more common for death to make the choice for us.

If your character is in a moment of forced or chosen passivity, it might work to transition to a passive voice. By doing so, you can slowly signal to your reader the change in the character’s attitude.

Here’s an example:

At the beginning of the story, Mara decides to move across the country. She packs her apartment, quits her job, and tells her friends she’s chasing something better. Every sentence in her life feels active: she chose, she planned, she acted. The move is hers.

Halfway through the novel, the language begins to change. The city is louder than she expected. The rent is higher. Her résumé is sent out, then sent out again. Interviews are scheduled, postponed, and quietly disappear. Days are no longer shaped by her decisions but by notifications and waiting rooms.

Eventually, things simply happen to her. The job offer is rescinded. The apartment is sold. Her belongings are boxed by strangers. Instead of Mara leaves the city, it becomes Mara is forced to leave. She isn’t steering anymore—she’s being carried along by events she didn’t choose.

In this passive stretch of the story, the shift in voice mirrors her internal state. Mara no longer feels like the author of her life but a character trapped inside it. By allowing the prose to become more passive, the narrative subtly reinforces the sense that control has slipped from her hands — until, perhaps, a later moment when agency returns and the sentences grow active once again.

Your story weapon: Mastering the balance of active vs passive voice

As you consider whether or not to include the passive voice in your writing, ask yourself about your own relationship with activity and passivity. To what extent do you feel like you lead your own life, and to what extent are you led? When it’s the latter, who or what is leading you? Are you chasing something or being called by it?

These questions and their answers can provide valuable insight into your own seasons of active voice and passive voice. That understanding and complexity, when gifted to your characters and your narration, is a wonderful tool to weave the tapestry of your story. After all, are you writing the story or is the story being written by you?

When your characters feel fully in control, the active voice will drive them forward with urgency and clarity. When they are swept along by circumstance, manipulated by forces beyond their control, or confronted with truths too large to face, the passive voice can give that experience weight and resonance.

Mastering the balance between active vs passive voices allows you to mirror the rhythms of life itself, giving your story a richer, more layered texture. It can also remind your readers that sometimes, it’s not just what happens, but how it happens, that shapes a narrative.

You are uniquely qualified to tell your story. Take control of the reins and find out more in one of my workshops: The 90-Day Novel, The 90-Day Memoir, Story Day